Mandy El-Sayegh Figure, Field, Grid

The Depot of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

1 November 2025 - 7 March 202606-01-2026

Say what you want about the Boijmans Depot but I love it. I love the building’s reflective exterior and the doofuses taking selfies in front of it. And I love that they installed little buttons so visitors can light up the various depot sections at will, giving the museum a diorama-esque allure that—in adult life—is usually reserved for peep shows. Or perhaps the word “museum” doesn’t quite cover the intents and purposes of the building, as the Depot is not strictly a museum, but rather, a publicly accessible art storage—and the world’s first one, at that. The Boijmans’ full collection is on display here, albeit in dormant form: the art works are stored in neat rows on shelves and racks, stripped from the reverence of their usual contexts (that is, formal exhibitions). It’s exciting to see an institution with the size (physical) and scale (social, cultural) of Boijmans Van Beuningen experiment with the definition of what an art space can be. Although the Depot does have formal exhibitions on show (more on this later), the presentation of the permanent collection prioritizes the whim of the viewer over the curatorial eye. Artworks are grouped together based on their material categories—“painting,” “furniture”—but are not assigned any meaning apart from that.

If you know your art history, you’ll definitely recognize a signature here and there, but if you’re a more casual visitor, most of the time you’re likely to have no idea what you’re looking at. In a way, the experience of visiting the Depot is not unlike going window shopping at a high-end mall: the novelty of seeing culturally relevant (and expensive) things up close, and “off duty” at that. Sure, there’s an element of object fetishism here, but it’s a format that works: the interactivity of the Depot’s set-up entices people to spend time with artworks that they would otherwise potentially blaze past. If no artwork is given a central platform in a renowned collection (think Sunflowers, think Mona Lisa), then the viewer isn’t given a spatial suggestion as to what artworks to prioritize during their visit. I like how the Depot democratizes its collection this way. And I’m thrilled to see the concept of interactivity explored through analog means, for once: I’m tired of scrolling through digital “environments.” Rest assured I didn’t download the Depot app to “enrich” my visit because there was already enough to see without it.

Mandy El-Sayegh’s show “Figure, Field, Grid,” for one. In addition to its permanent collection and thematic group shows, the Depot has allotted one of its galleries to rotating solo shows by individual artists who have not exhibited in the Netherlands before. El-Sayegh’s is the first one in this series. Before exhibiting at the Depot, El-Sayegh showed work at Art Basel (2024) LACMA (2023) and SculptureCentre (2019), among other venues, and received an MA in painting from London’s Royal College of Art (2009). The concept of the body—or corporeality, to echo the more academic term her gallerist Thaddeus Ropac uses—is central to her work: she refers to her canvases as “skins.”

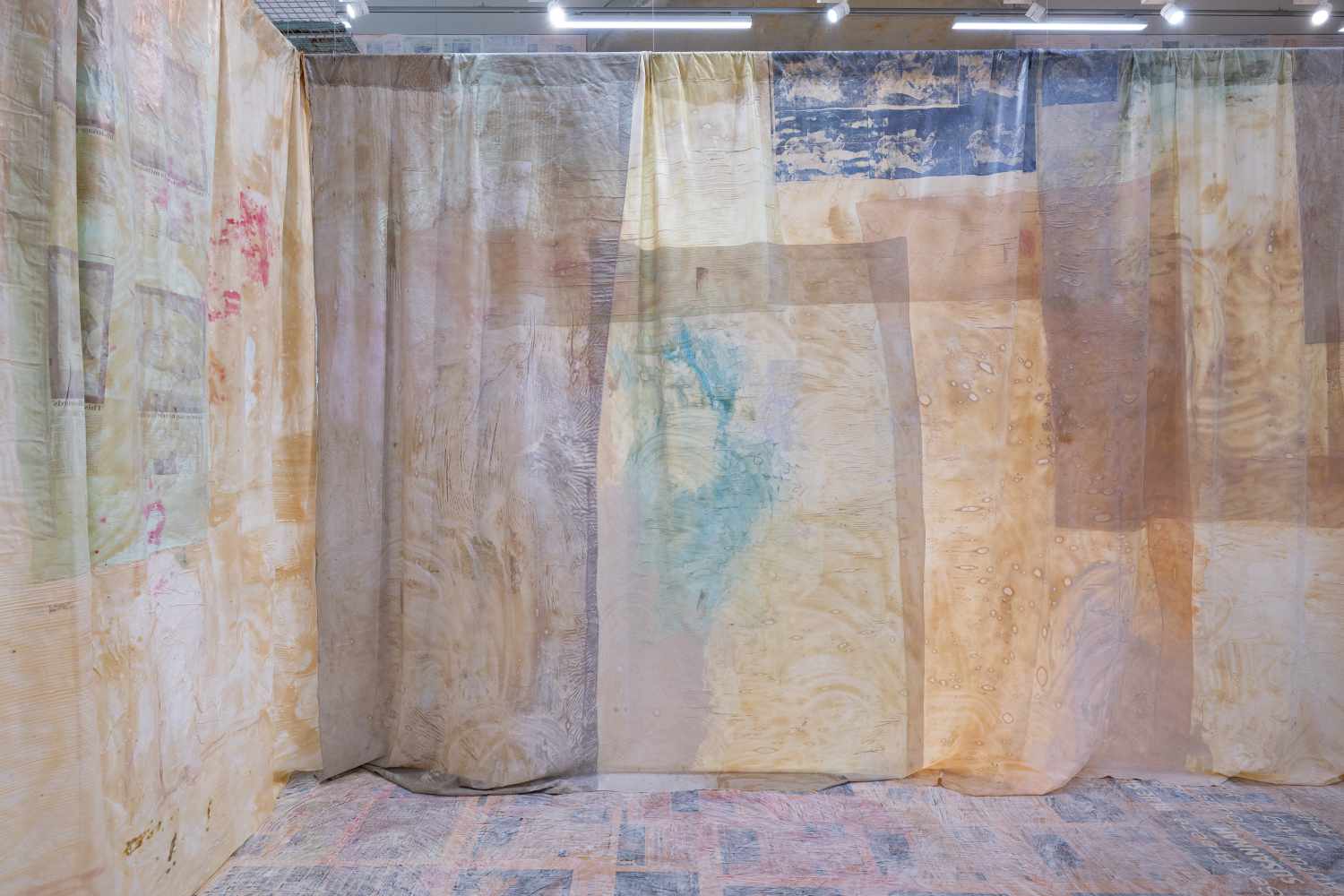

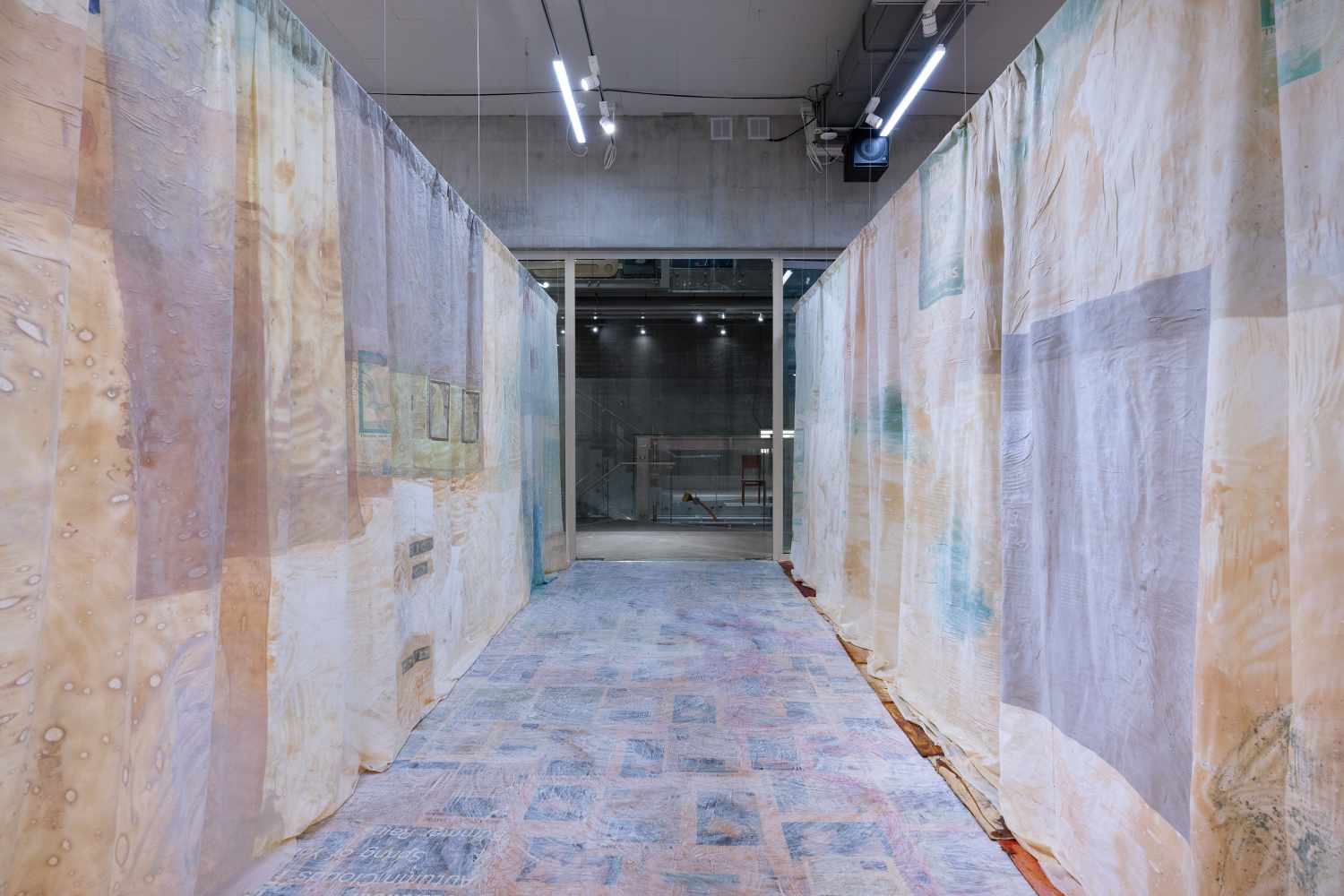

For “Figure, Field, Grid,” El-Sayegh used the entire gallery space on the Depot’s third floor as a canvas. The floor is covered in latex panels, many of them doused in red paint, and similar, albeit much larger panels dangle from the ceiling, effectively functioning as room dividers. I initially feel a sense of thrill upon entering the gallery, as if I’m passing into a different world. But once beyond the latex panels, in the main area of the exhibition, I can’t help but feel underwhelmed. The walls of the space are covered in, alternatively, newspaper clippings with incendiary headlines and advertisements for high-end jewelers like Mikimoto and Tiffany’s. Hey, I already know this world! And the (apparent) juxtaposition between reports of suffering and images of supreme wealth strikes me as obvious. Money, media and violence: sure! They’re all connected. What else is new?

But I can’t imagine El-Sayegh’s vision being that simplistic. And indeed, it isn’t. The exhibition’s title, “Figure, Field, Grid,” refers to Rosalind Krauss’s concept of the “expanded field,” in which the “figure” is seen as the starting point of abstraction and the “grid” as its definitive endpoint. El-Sayegh challenges this concept by using the grid as a canvas for non-abstract figures. To put it plainly, the figures that feature in El-Sayegh’s show are anything but abstract: they show the human body in extremely opposing levels of distress, from the doll-like pose that Anya Taylor-Joy strikes for Tiffany & Co to, further down in the show, pictures of US soldiers torturing Abu Ghraib prisoners in Iraq. El-Sayegh took these images from various online and offline news outlets and put them together in a neat, repetitive collage on the gallery walls—the show’s titular grid. Shown this way, the advertisements and the harrowing images of military violence appear to merge into one, a single skin rather than two separate ones. In certain presentations this combination could’ve been too jarring to metabolize (or worse: too didactic), but the installation is laid out in such a way that the viewer only gradually discovers the more viscerally violent images in the show. This isn’t to say that El-Sayegh tiptoes around her subject matter in an anodyne way, but rather, that she allows the viewer to discover what her work is about at their own pace—even if this means they have to spend a longer time with the work to feel what it’s doing. Let me just say that my initial reading of the show (“let’s show the people that The Media are in on it!”) was wrong.

(By the way, a word about El-Sayegh’s reference to Krauss: I don’t mean to imply that an exhibition instantly becomes good once the artist demonstrates a certain theoretical underpinning to their work. Some of the best artworks out there are created entirely without academic influences and besides, I’ve seen enough insufferable grad show works about “tentacular thinking” and “the rhizome.” But El-Sayegh is clearly doing something exciting here, at least if you ask me, and I appreciate how her technical treatment of the violent subject matter prevents her work from becoming sensationalist or moralistic. As a viewer I felt both were respected and challenged by the space that she built).

What I liked best about “Figure, Field, Grid” is that the work, while clearly profoundly rooted in politics, isn’t obsessed with its own moral integrity. El-Sayegh offers you a new way of thinking about how images of violence are mediated without screaming in your face. And she incorporates one of the Depot’s collection works (Warhol’s The Kiss (Bela Lugosi) from 1962) in a poignant way. The image of Bela Lugosi as Dracula, like the violent media images elsewhere in the show, evokes the notion of bloodlust, though Warhol’s reproduction is situated in the (relatively) safe realm of fiction. This, of course, is in stark opposition with the newspaper clippings that El-Sayegh reproduced, all of which communicate painfully real types of violence. There’s something wry about seeing a canonical vampire like Lugosi’s in the same space as an image of a war prisoner, but it’s exactly this wryness that makes El-Sayegh’s show uncomfortable (in a good way) rather than perfunctorily “with the times.”

Another thing I loved about the show: the light in the space is installed in such a way that the viewer, when walking past the dangling canvases, casts shadows on their surfaces, thereby briefly becoming part of the work. Some visitors (myself included) took pictures of their own shadow covering El-Sayegh’s latex skins and when I caught myself enjoying this I thought: ha, she (that is, the artist) is brilliant. Incorporating autonomous solo shows in their program is a bold choice on Boijmans’ part, since the spirit of the guest artist’s work—which, in El-Sayegh’s case, is clearly activist in nature—might pose a challenge to the casual day tripper visiting the Depot to see a Thonet chair on a shelf. But in this time of museums taking on an increasingly didactic approach to their audiences, it’s also a good choice, because at least the Boijmans is not underestimating their visitors’ capacity to grapple with the unknown. During my visit, a Dutch family entered the El-Sayegh show and although they loudly proclaimed to “not get” the work, they spent a good 30 minutes making sense of it together. Audiences don’t need to be lured into engagement by presenting art as a lesson. You just have to show them something interesting. Boijmans does that, and the Depot does that, and I’m excited to see what the building’s gallery space will look like next.