June Crespo their weft, the grass

1646

6 September – 3 November 202401-11-2024

My favorite part about my time in Madrid was, surprisingly, not Madrid, but a sudden connection to the Basque Country. Even though I’m Spanish, I didn’t live in Spain until 2022 when I spent four months in a study program in the capital. Most of my classmates were from Bilbao, and their work was buzzing at a completely different frequency than mine. Maybe my excitement about this new scene was accentuated by speaking about art in another language than the Art English I often encountered in Amsterdam. These kids were doing sick work, often along the lines of: “I drove down the highway with an angle grinder and stole some metal from the guard rail that I made a cast of, then I dug a pit in the forest, lit a fire, tossed in the castings and these are the melted remains. No biggie.” There was energy in the air. In this Basque scene, performance and sculpture seemed to go—almost compulsorily—hand-in-hand.

During those months, my friends took me on road trips and generously taught me Basque-core 101 (think of the relationship between sculpture and landscape, a quasi-religious affinity for industrial materials and a deep feeling of identity and belonging). As I slowly started to understand the nuances that informed their work and lives, I also got a crash course in the roots of Basque modern and contemporary art. There were the headliners of the 1950s Jorge Oteiza and Eduardo Chillida, who preceded the Gen X crowd Sergio Prego, Ibon Aranberri and Itziar Okariz (*icon,* who I often think about when peeing outdoors). Bridging to the present were artists like Nora Aurrekoetxea Etxebarria and June Crespo, who provided an exhilarating and queered revisitation to this earlier lineage.

Crespo, especially, was a bit of a rockstar for my Basque friends, and such a fan base consisting of Gen Z lesbians with an old-school punk ethos and a soft side for poetry was a green flag. Crespo has been busy recently with solos at the Guggenheim Bilbao and CA2M Madrid. As a De Ateliers’ alumna, she’s also been present in the Dutch art scene (you might remember “Am I an Object” at P////AKT in 2021). A show of new work, “their weft, the grass” currently at 1646 is not only a continuation of Crespo’s solo “They Saw their House Turn Into Fields” at CA2M, but inaugurates a “new long-term collaboration” between the two spaces. I'm curious about what such a collaboration might entail, and I’m hoping 1646 won’t simply start repurposing institutional shows on a smaller scale. The promotional materials for “their weft, the grass” included a work that is not present in the space, which seemed not so much a sign of truncation as kind of…edgy?

At CA2M, Crespo presented her sculptural work exclusively in tension with the gallery walls, leaving the ground entirely bare. In The Hague, the works are also strapped to the walls, but the formalist exploration of weight and constraint present in the previous show doesn’t seem to be the main focus. Crespo’s sculptures are made of truck canvas, ventilation pipes, fiberglass, epoxy resin, aluminum and stainless steel casting, carbon fiber, lashing straps and textiles. My friends were right, June Crespo is some sort of rockstar with work that looks pretty badass: fragile, huge, sometimes tiny and alive.

According to the gallery text and much of the framing of the artist’s recent practice, the works developed from a collection of different flower species that Crespo gathered and scanned then expanded and distorted. In the production of her sculptural work, Crespo re-engages this archive of sorts by translating its content into new industrial formats that emphasize the demands and imperfections of the artist’s chosen material. Often, textiles are added to the structures like a skin. While this background calls attention to key elements in the work such as the collision between the organic and the fabricated; fragility and heft, I believe that reading Crespo’s show as an industrial translation of flowers also hides more interesting complexities at play.

Indeed, very little from the works on display maintains a direct connection to Crespo’s flowers, which is the first of my qualms with what appeared to be a neat curatorial framework focusing on the complexities of delicateness. Encountered in the doorway of the largest, lightest gallery, TW,TG (Iris) (2024) is a work that seems to immediately challenge such a reading. More than four and a half meters long and made of polyester resin with asphalt, it resembles skin but of a preserved or cured sort, stretched from floor to ceiling with straps and resting softly on a piece of foam like a lil’ pillow (sexy). In the same space, two cast metal pieces of around three meters—TW,TG (Acanthus I) (2024) and TW,TG (Acanthus II) (2024)—appear as though they are trying to swim headfirst into the gallery as they hang from the walls with tensed-up straps that seem to defy gravity or at least defy the wall itself. Given the sheer size and physicality of these works, the titles and their gardener’s almanac references start to feel like a Trojan Horse for a fragility narrative (“what you see, what you sense, is not strength, it's tenderness”). And so I couldn't help but wonder: are these tensions implicit to the work or fabricated by the surroundings? What role does the gallery space play in mediating (and possibly re-poeticizing) the works’ contrast of textures, weight and autonomy? The scale and the rawness of the materials in fact bring a feeling of certainty to Crespo’s sculptures, while their dominance in the space also present contradictions.

Perhaps these contradictions are what make the work almost ghostly, like there’s a previous life or iteration that struggle against the way in which they are preserved in the gallery. Yes, there’s a connection here to the way a flower might be cataloged or pressed between the pages of a book, but then what to do with all the overflowing materials, the intense smell of truck canvas that permeates the space, the sense that these “bodies” are not fragile or precious, but unruly? What makes these works convincing is the possibility of decay and the way this adds tension to their being contained, strapped down. Each work seems almost unscripted, as though on the verge of some kind of evolution that the white cube setting (and at times Crespo herself) seem to muffle through emphasizing a research-based poetic gesture. The dominance of the flower references seem ultimately like a distraction from the sculptures’ actual potential as transformative objects.

After viewing the exhibition, I sat in the gallery’s typically-tiny Dutch stairway and spent an hour and a half reading the catalogs available (from Crespo’s solo show “Vascular” at Guggenheim Bilbao, as well as the exhibition at CA2M). I was especially drawn to Crespo’s diaristic notes included as an interlude in one catalog essay: they allowed me to see the 1646 show as so much more sensual; as if the rhythms of daily life, its frustrations and joys were able to move through the cracks of the works. The sculptures’ raw transposition of the flower into something wilder, even grandiose seems indeed more vascular to me than intuitive or plainly physical; vascular as in the channels and veins through which fluids pass in the bodies of animals and plants. Canals. There's translation, and then there’s distortion, and then there’s the distortion caused by translation. These variations of canals are both devices and byproducts of Crespo's practice rather than the work itself. I’m thinking of the layered and wrapped fabrics of the Acanthus I and II variations: folded, stacked, ready to be swapped.

Crespo’s diary-like entries, where prose mixes with poetry and to-do lists also felt like a collection of clues. This intimate writing didn't just open up new possibilities for a stronger, intentionally bending and distorted body of work, it led me back to the Bilbao-based Crespo fanclub, whose fascination wasn’t so much about finding a contemporary sculptor to carry on and reinvent a Basque tradition of experiential, large-scale artistic making, it seemed like a more radical and also more personal form of identification. At one point in the diary entries, Crespo writes, “What could a lesbian monument look like?” (🤔).

I don't think of Crespo’s sculptures as evocative objects in space, but instead as objects in relation to a body, my body, Crespo's body in space. This aliveness relies on the circulation of images and gazes allowing us to dance around an object we might know and recognize as we change with it. A clear example of this quality is the use of reflective textiles in TW,TG (IV) (2024) & TW,TG (III) (2024), in which every subtle change in the visitor's position alters its image as the light changes its colors and shades. When you repeat something enough times, that something transforms itself. In the end, the magic is not inside the gallery, but present in the possibilities that Crespo's work generously offers in the exchange of body&object: to look up, look through, look down, around, with, at and so on.

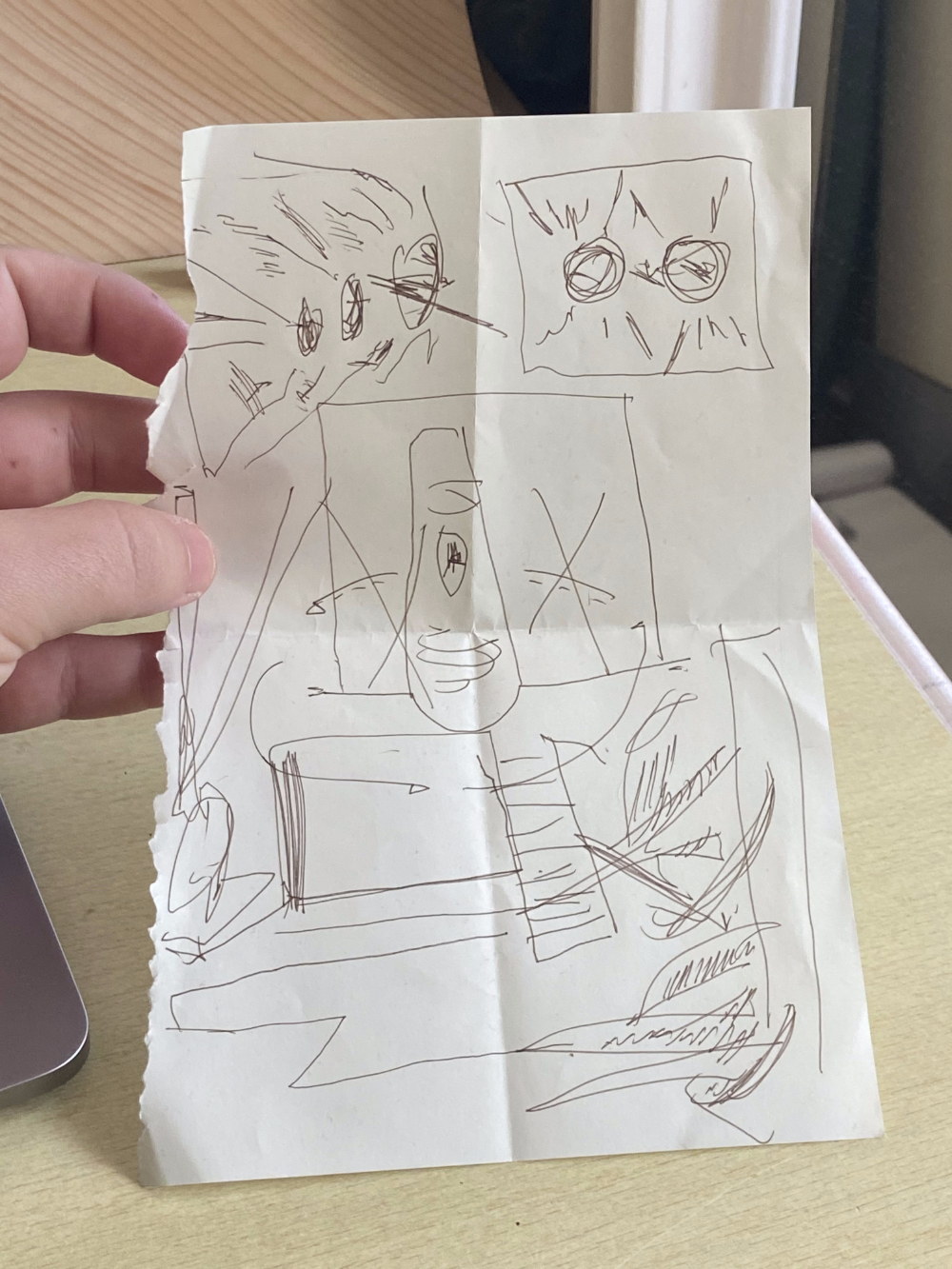

A few weeks after visiting the show, I sketched what I remembered from the sculptures. What lingered with me was not the clean and controlled situationship in the gallery space, but a more intense and maximalist presentation. This representation—crowded, overlapping, radiating, looking out—made me realize that I would have liked to see all the works in one cramped space, a sort of labyrinth of tension, unresolved and entangled. Maybe what I was imagining was Crespo’s studio. Ultimately, June Crespo works with mundane images that become visceral. All these functions of acceptance, meaning, familiarity and proximity are built through distance; when language fails. It is in this way that Crespo's flowers are flowers. Just so you know, there weren’t any flowers in the backyard of 1646. I was meant to see a bunch of other shows after “their weft, the grass” but instead I biked to the beach. It was a perfect day.