Marina Abramović Marina Abramović

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

16 March – 14 July 202425-06-2024

When Tangents heard there was a Marina Abramović retrospective opening at the Stedelijk Museum titled “Marina Abramović,” we were there in an Amsterdam Minute: at least two months late, too late to be topical, but not so late as to be entirely irrelevant. What follows is a spirited discussion between Tangents’ managing editors Becket Flannery, Annie Goodner and Isabelle Sully about the artist’s body of work, its political posturing, the difficulties with restaging work about one’s own body and ability to suffer and Carrie Bradshaw’s dating as performance practice. Gilles Deleuze apparently said “good destruction requires love.”

Annie: There are actually quite a few excellent shows up right now in the Stedelijk’s airier and more lively upstairs gallery spaces (stanley brouwn, Ana Lupaș, Wilhelm Sasnal). I was struck therefore by how isolated (conceptually, contextually) the Marina Abramović blockbuster exhibition seems to be. Descending into the exhibition’s basement galleries, the first thing one encounters is a crystal-encrusted portal (Selenite Portal, 2022) through which one is supposed to pass (or pose for selfies). (Editorial note: Since we first visited the exhibition the portal has been roped off; now visitors can only circumnavigate it). This work is positioned for drama and engagement (well, not so much now), and while it leads you — ostensibly — into Marina’s ‘‘world,’’ actually you arrive at this odd interstitial area with the wall text on one side and a content warning on the other. Small frames off to the side hold a collection of simple, delicate drawings on luxury hotel stationary (Nomadic Journey, 2023) that trumpet a fundamental element of the Marina mythology, that of her ‘‘nomadism’’ (though now she’s traded in the beat-up Citroën bus for the Chateau Marmont). There’s an ephemerality to these works, hints perhaps at some kind of process or a repeating gesture — akin to the archival footage in other parts of the exhibition — but they also don’t tell us much about Abramović’s approach (besides the denotation of luxury). If there’s a hint at all, it’s that the works in the exhibition arrive fully formed: there are no sketches, no rehearsals and very few doubts.

Becket: I’d say those drawings would be ephemeral, if they weren’t digital prints of the originals. They fit oddly into the exhibition spaces, which is perhaps why we find them in this threshold between the galleries and the selfie-spot: they have the materiality of the gift shop.

Annie: l’ll probably say this a lot here, but the works are so often decontextualized. In The Lovers (1986), for instance, Marina and Ulay interpreted the Great Wall of China (the setting for their last collaboration) as having a magnetic pull, constructed in alignment with the earth, rather than a structure based on military or financial demands. There’s a neutralizing effect throughout Abramović’s oeuvre that leaves me to surmise a lack of deeper engagement with a political context. Social concerns are not Abramović’s focus at all (despite gestures towards them throughout her career). The primary method at play across Abramović’s body of work is the magnetic pull of the artist herself. We are led to her by her. Some people are fascinated by this, while others are not, but either way the work depends on Marina as the lodestar. Sometimes the lack of a clear context combined with the unedited, somewhat harried or not entirely coherent nature of her early live performances is quite moving (I’m thinking here of Thomas Lips (1975) in which she consumed a large amount of honey with a spoon, then cut a pentagram into her abdomen and laid atop a cross made of large blocks of ice). There’s a messiness, a kind of unvarnished desire, less emphasis on purification or transcendence.

Becket: The Stedelijk has staged some great shows in the last few years, but it has also turned hard in the direction of hypebeast nonsense. The result is paradoxically dull. Sometimes it feels like a PR firm that happens to have an art collection, to the point where I’m not sure if the institution itself has any idea why these shows are valuable or worthwhile. I get that sometimes we just want to see something because a lot of other people want to see it, but at some point an art institution needs to make a coherent argument that doing so would be, y’know, important.

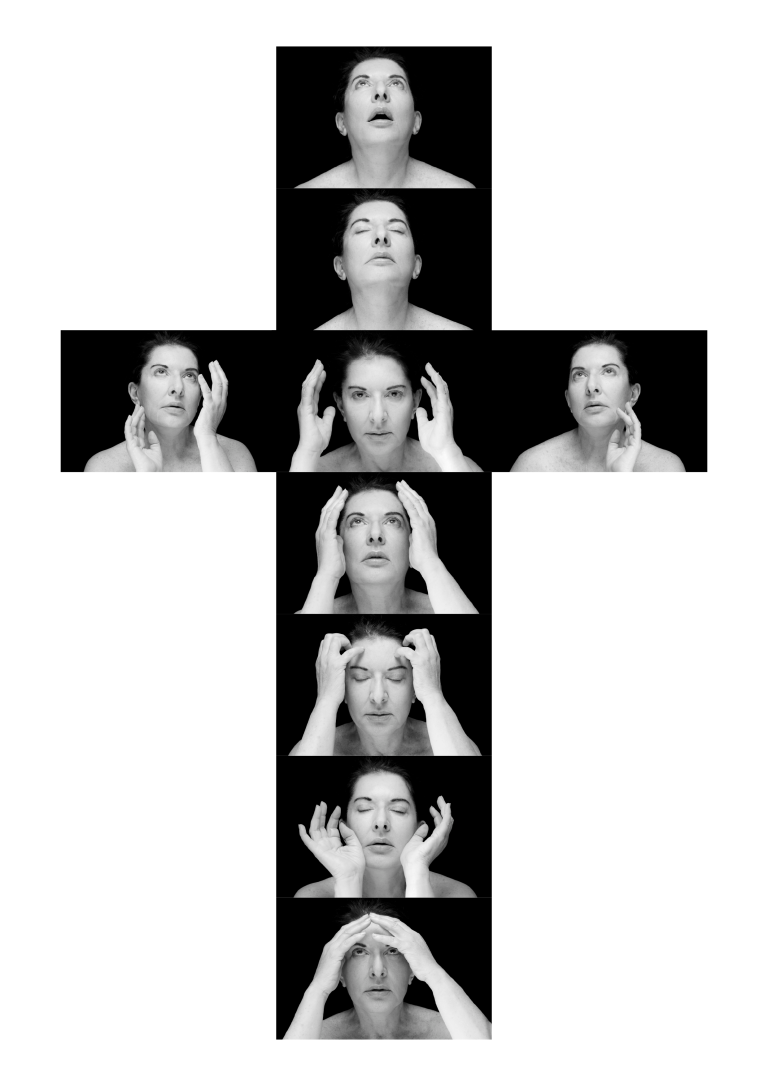

I do think Marina is an artist with a very different relation to the public than most. Call it “the Santa Claus factor,” an overly-familiar attitude towards certain individuals whom we feel we already know through their semi-mythical status.¹ There’s a reason why we call her Marina, and a reason that the “documentation” (if we want to call it that) of The Artist is Present (2010) features two video grids of people’s faces as they gaze, fidget, cry, act out or vamp it up while sitting across from Abramović. In a way, I’d love to see the Marina that her fans see; it seems more generous than the other two filters that the show gives us to view her work, namely the historical Abramović in photographic and video documentation and the ersatz theme park constructed out of newly minted props, tableaus, and re-enactments. Somehow this latter category even encompasses her actual recent work, such as Four Crosses (2019) or Five Stages of Maya Dance (2013/2016), large sculptural works which invoke spiritual traditions but contain nothing other than her own image: the Marina Abramović (Longevity) Method stripped down to its core equation. For me these are really the nadir of the show.

Annie: Abramović’s celebrity or mass appeal is also a necessary part of what she credits as the mainstreaming of performance art and perhaps that’s doubly the case at the Stedelijk, which must establish her superstar bonafides at the same time that it plays up her self-mythologized artistic beginnings in the scrappy Amsterdam of the 1970s. Of course, both of these things can be true, though the narrative of Marina’s ascent from the margins of new performance practice to the canonization of her method (and brand) is well-trodden, and I would argue not very compelling as a result. In an interview with Dutch public television about the exhibition, the Stedelijk director Rein Wolfs together with Abramović rehearsed the same historiography (or hagiography), which starts and ends with her iconic status as the “grande dame” of performance art.² The Stedelijk plays the role here of curator, historian and indeed hype man, identifying the ways in which Abramović imbued performance art with essential qualities like trust, endurance and strength (mental more so than physical), while also gushing over viral moments from her career, such as when Ulay sat down in front of Marina during The Artist is Present, provoking her to break her weeks-long glassy veneer. And yet despite the dominance of the retrospective to Abramović’s current practice, the artist herself regularly dispenses vague bromides like “don’t have nostalgia; we only live in present and in future.”³ Isabelle, we had been in the exhibition for about fifteen minutes and were looking at what we agreed was Marina’s best work: a live performance and multi-channel video in which her parents sat in the corner and watched her scrub the meat off a pile of bones (Balkan Baroque, 1997). And then you said: “Marina occupies all opposites.”

Isabelle: Detached from my immediate reaction upon visiting the exhibition, such a comment now reads like a compliment. Which is perhaps ironic, given that it leaves Marina again occupying an opposite, if only within the scope of my own feelings about her work: unrivaled aversion and a total love of indulging in it. But what I think I was getting at in that moment, which, it is important to note, took place in a room laden with the aesthetic symbolism of a nationalist agenda, was that Marina seems to signal both everything and nothing.

Annie: She’s said before that her father was a Communist — imprisoned before the Second World War, later promoted by Tito — but her mother was bourgeois (or a bourgeois Communist). All opposites.

Isabelle: For me this is epitomized in the discord between her early works, mostly made with Ulay and which continue to be art historical reference points generations on, and her present-day incarnation—which, it can’t be denied, is posturing as religiously poignant as the incarnate come. Within the Stedelijk exhibition, this discord was most pronounced for me through the choice to present an array of her durational performances at short intermittent bursts throughout each day. This opened up a series of questions that for me remain unanswered and unaddressed both within the exhibition and her practice at large. For instance, the pop culturally notorious work (thanks to Alexander Petrovsky and Carrie Bradshaw’s meet-cute in Sex and the City) The House with the Ocean View, first shown within a commercial gallery context at Sean Kelly, New York, in 2002, is anchored to a durational quasi-spiritualism. Abramović effectively entered into a twelve-day, self-imposed fast, during which she didn’t leave an aesthetically “pure” set modeled on a three-room apartment (bedroom, kitchen, bathroom) and “attempted to alter the energy in the room.”

Annie: Unlike the more abridged re-performances, the Stedelijk presented The House with the Ocean View in its entirety. I stopped by on the twelfth and final day of the performance, and while the room was slammed with people, there was a sort of empty artificiality to the space. In a rare moment of self-doubt, Abramović noted in the mid-aughts that it was a mistake to “put herself up on some kind of altar” during the original performance (as opposed to at audience level? What about the knife ladders?).⁴ At the Stedelijk, the performance space is still elevated like the original, but the performer — in her ascetic purple uniform, gazing out at the audience, her face a mask of exhaustion mixed with pleasure — seemed to be impersonating Abramović from The Artist is Present. And the audience followed suit, mimicking a kind of rapt attentiveness.

Isabelle: The performers bring up a second set of questions about duration and commitment when it is no longer Marina herself performing, but a group of individuals standing in, some of whom have trained at the Marina Abramović Performance Institute. These are questions surrounding, for instance, workplace safety and workers rights, questions that have entered the framework since the 1970s, when pushing the body to its literal extremes wasn’t a legal risk for the institutions endorsing the work. On the one hand, part of me thinks it is a necessary revision to the core (questionable) conditions of the work. On the other hand, part of me thinks why restage it at all?

Annie: Several contradictions also stand out to me in The House with An Ocean View, which carry through and are even amplified in its restaging at the Stedelijk. The formal structure of a theater play is evident in the work’s architectural elements, the raised platforms that present a tripartite domestic set piece in which Abramović acts out a series of simple rituals all to the beat of a metronome. Yet, the stated aim of the work — to present “a rigorous way of living and purification” that “would do something to change the environment and to change the attitude of people coming to see me” — is at odds with the theatricality, with the artificiality of the theater's fourth wall (overdetermined here as the ever-threatening knife ladders).⁵ The audience members crane their necks to watch the performance and performer—they are a traditional theater audience in this sense — and yet they are also supposedly participants in a purification ritual; they are the ocean view which holds the potential to create an “energy field”. If this work is theater, then it’s not a theater of the world outside of it, but a theater of Marina’s own personal drama — a drama that is apparently compelling enough to be reenacted. It was certainly not uncommon for artists (long before House...) to use the ritual of their daily or intimate lives as a space for political engagement. The work of someone like Mierle Laderman Ukeles and her maintenance art, however, was connected directly to a larger system of labor value.

There is no world outside of a Marina Abramović work, no entanglement with systems or structures. The energy field she wanted to construct with House… was contained within the gallery space, within the performance. Tellingly, when the work was “reperformed” in a Sex and the City episode the gallery press release (as read by Charlotte to Carrie) differed slightly from Marina’s stated aims: “By changing my personal energy field I am attempting to change the energy field of this room and perhaps that energy shift will shift the energy of the world.” (Carrie: “Good for her. So, Pastis for lunch?”)⁶ That Carrie finds a lover in spite of the heavy-handed, even stultifying surroundings is comic genius on the part of the show’s writers, which is perhaps the real artistry here and some insight into a different way of engaging Abramović: as strangely, darkly funny. For a moment we have a spark and a connection that links the interiority of Marina’s world to somewhere or something outside of it.

Becket: For me the question of re-performance is already present in the original work, actually; theater is always engaged somehow with repetition, and so if this work is “theatrical” it is somehow already asking whether this is a singular act or one in a sequence. Performing a work that is so much about total presence (and being present) has to be attuned to its own specific circumstances; and the conditions of a re-performance are that it is already a kind of after-image. I’d be very happy for that to become something in itself, to be more than a kind of living documentation, but perhaps that is better accomplished by the SATC episode, or at least that proposes a more interesting form of re-performance. In the context of the exhibition, I preferred the (recorded) documentation of the original performances that included some aspect of the audience. It was interesting to get a sense of what it felt like to see these works for the first time, in which the roles of the audience and performer were still being negotiated.

Annie: While the documentation prompts these kinds of early negotiations with spectatorship or agency, they seem ultimately overshadowed by Marina’s own starring role — her presence, in other words — and the risk-taking that role seems to always demand. Her performance Role Exchange (1976) in which she switched “roles” with a sex worker named Suze in Amsterdam’s Red Light District could be understood to most directly interact with systems of work, extraction, and performance. In reality, the work was a sort of cosplay limited to Marina looking the part, standing in a window, smoking. There was clearly a gambit for doing the sexual labor of a sex worker, but this role-swap was strictly performative — in reality, only two people came to Marina’s window: one person to ask after Suze, and another who didn’t want to pay the price. Sex work in Role Exchange is not a job, it’s a foil for Marina, described as a personal fear grounded in her “strict” upbringing. This work seems to play a big role in the Amsterdam imaginary of Marina’s career trajectory.

Isabelle: Someone told me last week that Marina had a brief stint in theater, through which she collaborated with the likes of Leigh Bowery. This aspect of her practice is largely unrecorded, mostly plotted out in her autobiography, where she describes in detail a project that saw her making magnetic shoes for rats so a cast of them could scurry up the metal sides of a set from below, so I was told. This project was never actualized because in the process of making the hundreds of shoes for rats, it became clear that they all had different foot sizes and it was simply impossible to design a standard shoe that would fit them all. There is something about Marina and taking things — though it may feel weird to say this given the sheer scale, economy and commitment to her work — way too lightly. This is so evident to me in something she said about the Sean Kelly show: “House With Ocean View was for me an experiment. When I came to New York, it was just after September 11, and I found New York so much changed. I found New York and people living here different, more emotional, more vulnerable, more spiritual.”⁷ Again there is this pointing towards a political context — one that completely reshaped the world — and no follow through. A hunger strike without a stated aim.

Annie: But also… What a canned line. It could be applied to any place, time, context. Returning to Balkan Baroque, which premiered at the Venice Beinnale in 1997, comparatively to all her other work, it seems to have something concrete at stake because she developed the video work and live performance in response to the Bosnian War. The performance of this work itself seems to exceed and also deny restaging: the physical conditions, the summer heat, the worms that apparently started to emerge from a pile of bones that Marina was cleaning. Of course, at the Stedelijk there was an attempt to re-create the mood in a darkened corner and the result is actually sort of absurd. We were laughing at the gigantic, fake prop bones together with the video work of Marina’s mother and father, like hammy, old-timey actors, and the artist herself dancing awkwardly in a white lab coat. I’m not sure if this is intentionally funny, but it was certainly baroque.

Becket: I do think the question of whether Marina is funny is kind of important. In being overly serious, there is a camp quality that emerges, perhaps belatedly. To paraphrase something that Nietzsche wrote long ago about Wagner: this retrospective seems worthy of an artist who, arriving at the ultimate pinnacle of her greatness, comes to see herself and her art as beneath her — when she knows how to laugh at herself.⁸ The crystals, the persona, the stagecraft could all be forms of performativity, and I certainly have a deep appreciation of camp, but I wouldn’t say it possesses much critical power at the moment. Rather than an argot, it’s become more of a vernacular, as Bruce LaBruce argued in his essay “Notes on Camp/Anti-Camp”.⁹ Camp performativity may be a tactic for revealing a norm or status-quo as a construction of hegemonic power, but it now just as often serves to belie politics entirely. In this context, it’s hardly a surprise that the far right is much “campier” than the left (maybe even historically, if the Wagner reference is any indication). The wink and nod of conservative camp is less about deconstruction than it is an illustration of that old saw, “If the world wants to be deceived, let it be.”¹⁰

Could Marina’s recursion to the self be a critique of the various figures who claim that only they can purify the body politic? That would be hard to read into this retrospective, in any case. One of the works I appreciated the most, although it has a very minor presence in the show, was Relation in Movement (1977), in which Marina and Ulay drive a little French Citroën bus in tight circles in a public square for the Paris Biennale. Abramović would shout the number of revolutions through a megaphone after each rotation until the piece ended when the car’s motor expired. The work follows some of the well-worn lines of the rest of her oeuvre: a potentially political form (a public square, a megaphone, a public demonstration, even the bus is a renovated police van) with no content. Still, there is possibly a parody here of the portentous meaning ascribed to other works, the only signifier being an arbitrary counting, the only closure a moment of mechanical failure.

Isabelle: In thinking about this anecdote of the rats, as well as her scrubbing clean the pavilion-sized pile of animal bones, as well as her atop a horse waving a white flag, as well as The House with the Ocean View, what unsettles me most about Marina is this utilization of the politics of purification coupled with the aforementioned symbolisms of nationalism. It feels like you’re in the midst of a scenario in the Hunger Games, where everyone is cloaked and kooky, pointing towards a politic while flirting with its aestheticization, yet still earnest in their investment in something, fighting even, but what precisely that is is never actually stated. What is strange in many instances within the show is that her claims to identity — whether the female body and its encounter with violence, nationality, her self-positioning as some kind of religious deity — actually seem to reject identity altogether. Or, at least, a subject position outside of a kind of taxonomy of categorical signifiers. This artistic strategy of evasion is also what enables the God-like status: God is everywhere and omnipresent, pervasive and ungraspable; ultimately, beyond critique.

In the end, the image that sticks with me most is the flutter of gold leaf as Marina looks directly into the camera, her face covered in a flakey layer of this luminous material (Portrait with Golden Mask, 2010). In 2012 she turned James Franco into a “living piece of art” by similarly covering his half-naked body in a layer of gold leaf. While wearing a lab coat and applying the leaf with tweezers, she talks about it as a “life material.” Given the substance itself and its application to the face, I can’t help but think of this work in relation to (celebrity) beauty trends aimed at fighting the signs of aging — the crazed gold leaf facemask treatment as one overt connection. In light of this, I understand these attempts at life-extension — from imparting her performance method through a self-built institute in service to sustaining her artistic legacy, to recently launching her own skincare brand aimed at “rebooting your life” — as her interest in duration repackaged.

Here, if we acknowledge her earlier works for the role they played in reshaping the conversation around the body and performance art, then it has to be agreed that somewhere along the way something stopped computing. Much like her cream, a formula is tried and tested within her practice — submit the body to forms of violence, endure as it resists, overcome fear to reach higher consciousness — however these experiments slowly moved away from upending the status quo and towards affirming it. The Marina Abramović industrial complex is busy at work. While easy to dismiss, to focus on her current-day exploits is to take seriously the question the Stedelijk is posing by staging this exhibition in 2024: Why Marina now? It is a retrospective after all, we follow a practice through the years and we arrive at the present day. Perhaps her relevance today can be found in an embodied critique of celebrity and wellness culture and of the cult of the individual within late capitalism — the fear of aging being her new driving force (something arguably vulnerable and human). To believe this, though, satire and subversion would need to be regularly utilized tactics throughout the practice. But considering the evidence laid out before us here, I am still not so sure just how conscious she is of the joke.

Becket: I couldn’t say precisely why the Stedelijk thought a Marina Abramović show was particularly relevant at the moment. For me, however, it dovetails with the conservative populism of the last elections. I recently read about the motto of the new cultural policy in Friesland, as determined by the BBB-dominated¹¹ Provincial Council, which translates to “fewer carrots, more frikandel.”¹² In reality, it’s going to mean more of a starvation diet, as the budget is simply being cut by almost two-thirds, but the shift in emphasis indicates a preference for the more consumable forms of art/food. Nonetheless, I don’t think the populist wave of the recent elections pushed the needle of the Stedelijk much; they were already heading down this road since the beginning of Rein Wolfs’ directorship. Wolfs' previous tenure at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn was marked by shows around figures like Beethoven, Michael Jackson, and Goethe, and big solo retrospectives like the Martin Kippenberger show (all from 2019, his last year there). The Bundeskunsthalle is a very different institution from the Stedelijk, but that’s a lot of cultural diplomacy to unlearn. Wolfs seems most comfortable when an exhibition is at a safe distance from the edge of the cultural conversation, opting for established importance over relevance. I wouldn’t compare Marina Abramović to frikandel, that would be unfair. But The Artist is Present was a kind of golden ticket for an institution like MoMA: a historically important artist, a viral phenomenon, a public relations jackpot.

Isabelle: As evidenced by the self-congratulatory move of the curator to sit down as the last person opposite Marina: a chuffed acknowledgement of each other, a knowing “our work here is done.”

Becket: Maybe it’s unreasonable to expect an institution like the Stedelijk to resist the temptations of such a combination of prestige and exposure, but what worries me more is the institution’s disinterest in even the attempt at an argument for the show’s relevance. The Stedelijk’s last heavily-promoted, big-budget exhibition, Anne Imhof’s YOUTH, followed the formula to the point of grotesque cynicism, if not quite self-parody. Why bother with making a case on the merits when you’re just counting the likes?

- Chris Kraus, “L'hommage américain à Baudrillard,” Le Nouvel Observateur, July 23, 2007, http://referentiel.nouvelobs.com/file/233/325233.pdf.

- “Kunstenaar Marina Abramovíc leidt haar opvolgers zelf op,” NOS niewsuur, March 13, 2024, https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/video/2512665-kunstenaar-marina-abramovic-leidt-haar-opvolgers-zelf-op.

- Aurora Prelević, “Marina Abramovic on Yugonostalgia,” The Believer, October 1, 2019, https://www.thebeliever.net/marina-abramovic-on-yugonostalgia.

- Judith Thurman, “Walking Through Walls,” The New Yorker, February 28, 2010, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/03/08/walking-through-walls.

- Marina Abramović, “The House with the Ocean View,” 2002, MoMA, accessed June 15, 2024, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/243/3129.

- Sex and the City, Season 6, Episode 12, “One,” directed by David Frankel, aired September 14, 2003. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5JvdsNpkMcU.

- Marina Abramović, “The House with the Ocean View,” 2002, MoMA, accessed June 15, 2024, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/243/3129.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals, Walter Kauffman ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), p. 99.

- Bruce LaBruce, “Notes on Camp/Anti-Camp,” Nat. Brut, no. 3: April, 2013. http://www.natbrutarchive.com/essay-notes-on-campanti-camp-by-bruce-labruce.html

- Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, Volume III (London: The Everyman Library, 1932), p. 328. “Si mundus vult decipi, decipiatur.”

- BoerBurgerBeweging, or Farmer-Citizen Movement is a socially conservative political party that swept Dutch provincial elections in 2023.

- Aan Dirk van der Meulen, "Het nieuwe cultuurbeleid van provincie Fryslân: wat minder wortel en wat meer frikandel," Leeuwarder Courant, April 19, 2024. https://lc.nl/friesland/Nieuwe-cultuurbeleid-Frysl%C3%A2n