Sergei Eisenstein The rhythm of ecstasy: the sex drawings, 1931-1948

Ellen de Bruijne PROJECTS

12 July – 4 August 202403-09-2024

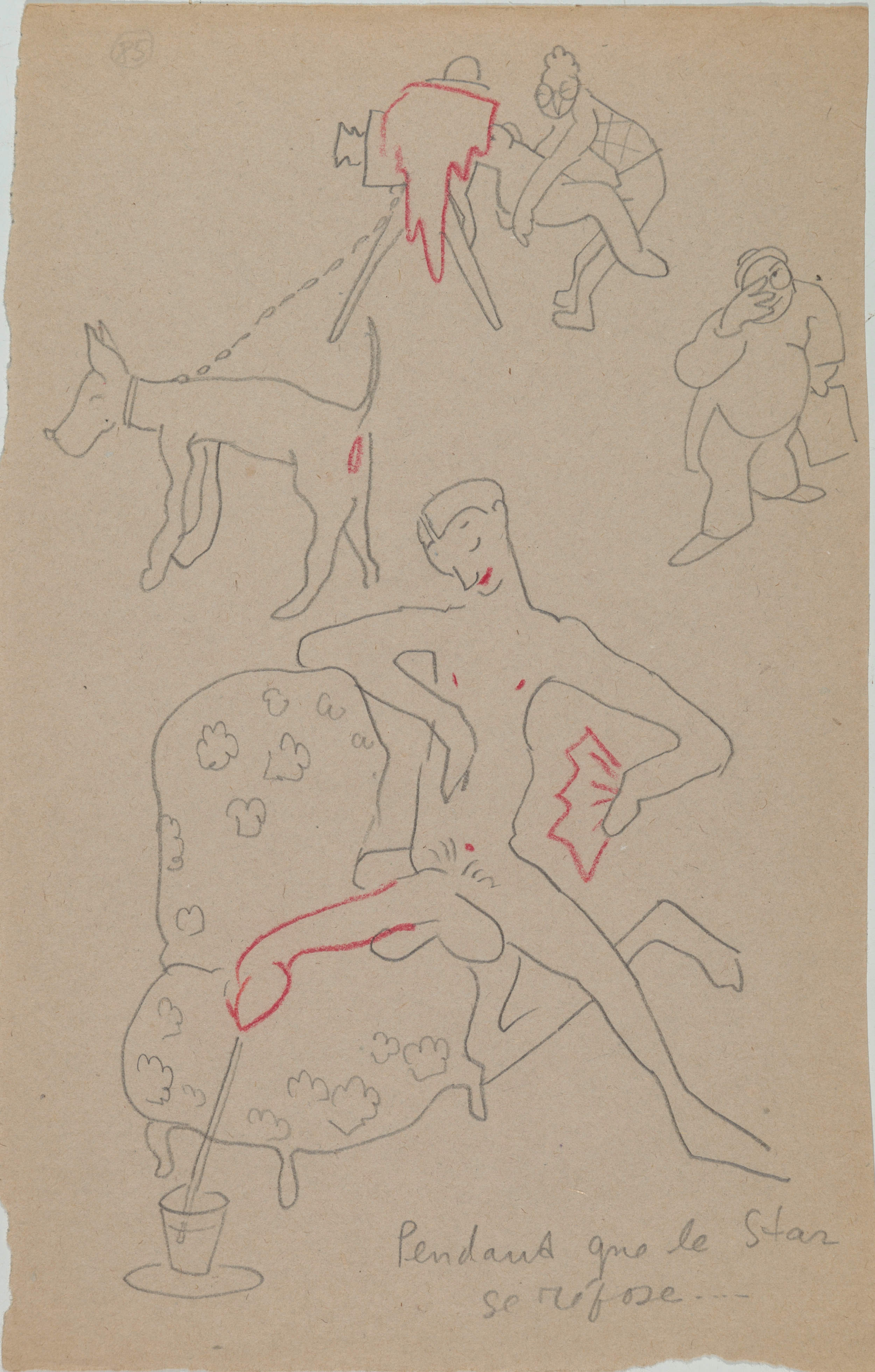

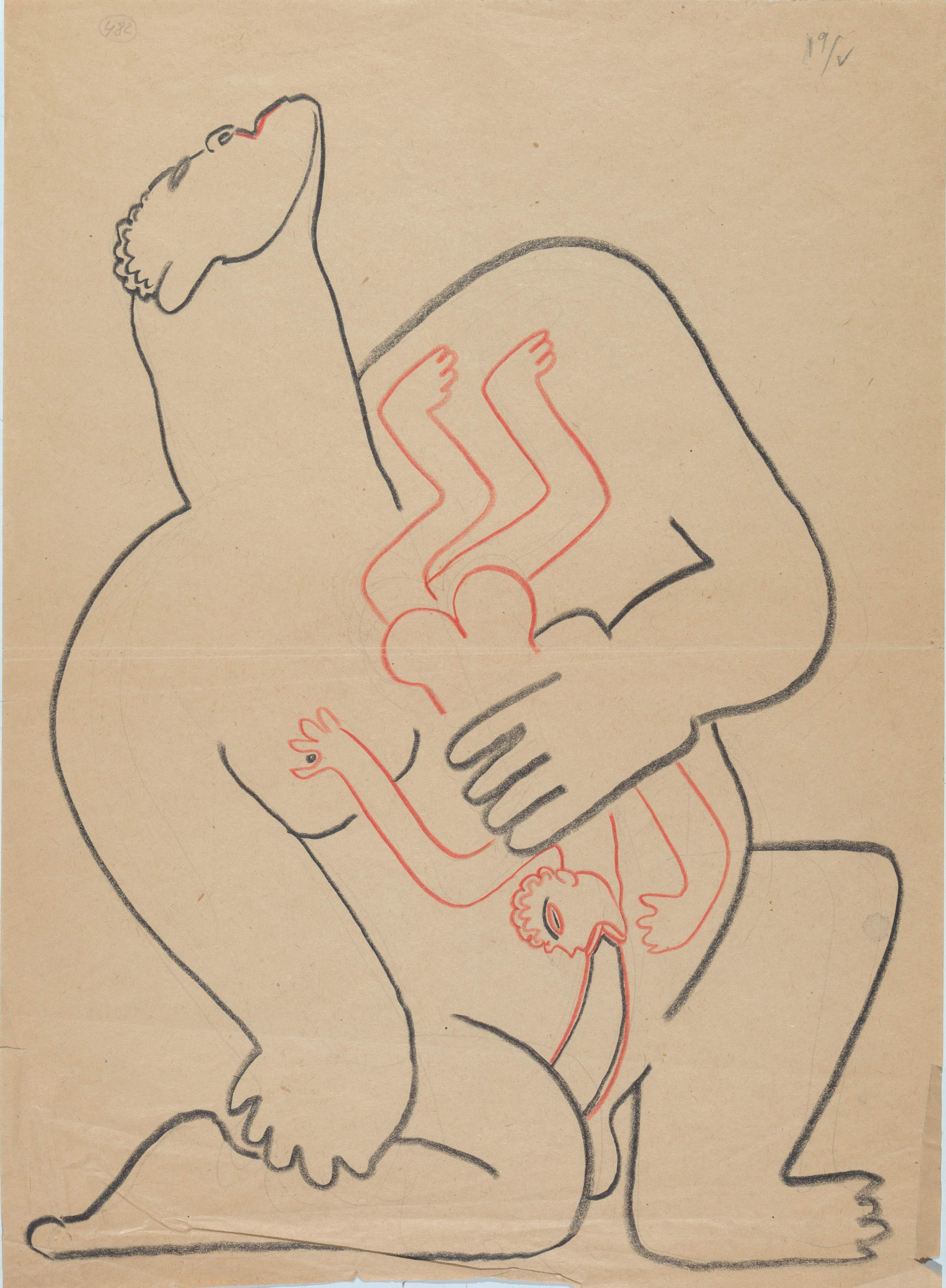

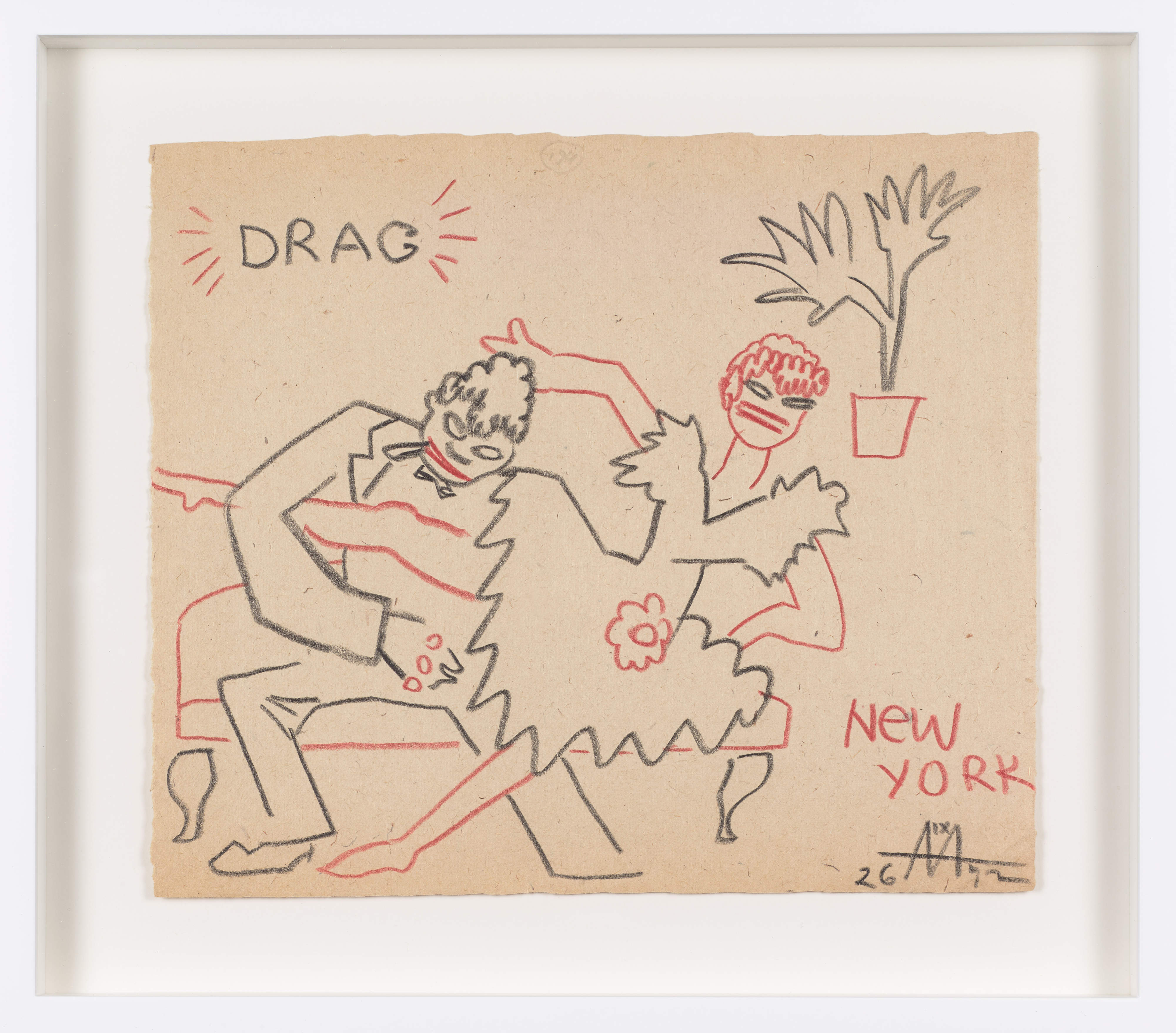

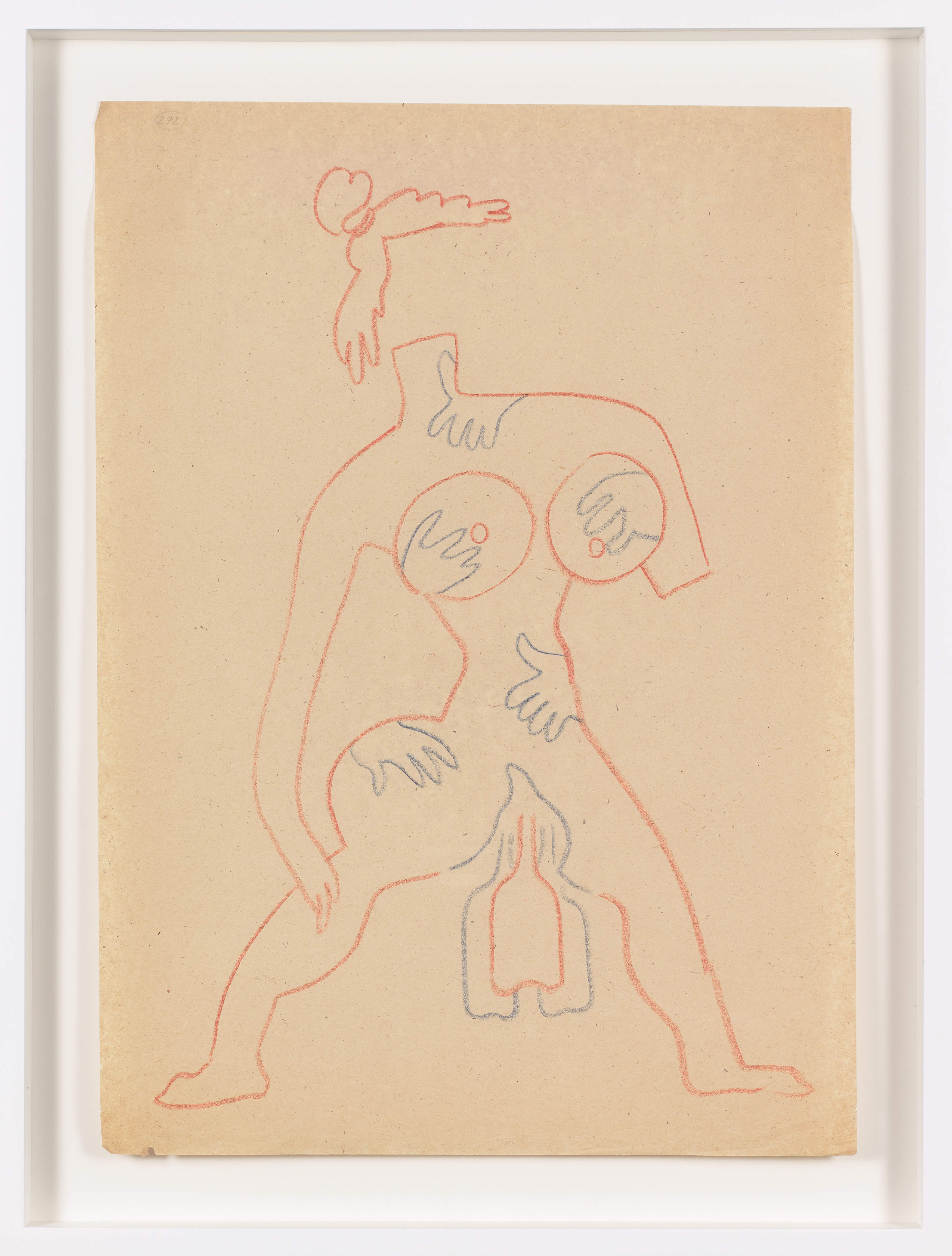

Sex drawings. Lots and lots of sex, in drawings on paper. A huge chunky guy with a thick, stretched-out neck holding a tiny figure, the size of his arm, upside down so they can suck his cock. Busty lady fucking a tree, various animate branches doing different kinds of pleasuring work on different parts of her body. Orgies. A scene from a drag show in New York. A languishing post-coital embrace on a bed with checkered sheets. Men with red lipstick. Men in uniform. Men taking their uniforms off and getting down to business. Animals. Including rams wearing masks with big erect cocks for noses. A naked person lies back with legs spread wide open, inviting one of the newly endowed masked rams in.

Bodies get all tangled up with each other. Merge into each other, undo each other. They expand and shrink. Get fragmented, dislocated, multiplied. They transmute; growing tails, wings and second heads, becoming botanical with roots and branches. A woman in a top hat and thigh-high stockings spreads out and reaches her hands and feet deep into the huge vulvic orifices that have opened up in the torsos of four surrounding figures; they receive her with joyous exuberance, and the caption reads “madame feels cold.”

Cocks are energetic entities up to all sorts of things. Some of them have faces or little arms or legs of their own. One is covered in stars and walking a tightrope at the circus (the tightrope itself is suspended between two erect cocks). There are scenes from pornographic film sets in the interwar years: a red-lipped performer is taking a break between scenes, fanning off to cool down, their enormous red cock sipping from a glass of water with a straw. Gotta stay hydrated. Someone else is on set getting ready for a scene, powdering his nose, while two assistants are kneeling at his feet; one polishing his boots, the other polishing the head of his cock.

Quickly executed on scraps of paper that are now yellowed and brittle, there are hundreds of these drawings by the Soviet filmmaker and theorist Sergei Eisenstein. A selection of them was exhibited over the summer at Ellen de Bruijne PROJECTS in Amsterdam.

Nobody told me Eisenstein was queer! Certainly not when they taught us about him in film studies and art history units when I was an undergrad. He was the daddy of Soviet montage theory and practice: important, monumental, serious. Turns out he was also serious about smut and nonnormative sexuality, and it was hardly a secret.

A lot of the sex drawings, and a lot of Eisenstein’s theoretical writings on sex and what he called “ecstasy,” come from 1931–1932, when he was living in Mexico. He had previously travelled to Hollywood with a lucrative contract from Paramount Studios, but things hadn’t gone according to plan. In a climate of rising antisemitic and anti-communist hysteria (which saw the pamphlet Eisenstein, Hollywood’s Messenger from Hell come into circulation, describing the filmmaker as a Bolshevik Jew who had been sent over to brainwash the American population with Soviet propaganda), Paramount ended up cutting ties with him.

Before leaving Hollywood for Mexico, Eisenstein had hung out with Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse (there are photos of this). His later writings on Disney are, I think, a good accompaniment to the sex drawings. He was excited about what he called “the amazing, elastic play of the contours of Disney’s images.”¹ The mutation and self-dissolution of forms; the elasticity of bodies: “With surprise — necks elongate. With panicked running — legs stretch. With fright — not only the character trembles, but a wavering line runs along the contour of its drawn image.”² He was fascinated by the way “Disney’s beasts, fish and birds have the habit of stretching and shrinking. Of mocking at their own form, just as the fish-tiger and octopus-elephant of Merbabies mock at the categories of zoology.”³

Eisenstein didn’t want to overstate the utopian potential of this liberation from categorical fixity and ossified form. He wrote at one point that “Disney is a marvellous lullaby for… the oppressed and deprived. For those who are shackled by hours of work and regulated moments of rest, by a mathematical precision of time… Disney’s films are a revolt against partitioning and legislating.” However, Eisenstein continued, “This revolt is a daydream. Fruitless and lacking consequences.”⁴ Far from changing the world, Disney cartoons could function as counter-revolutionary lullabies. And yet, Eisenstein remained attached to the possibility of reimagining bodies, identities, and relations through forms of animistic mutability, and what he termed the “unique protest against the metaphysical immobility of the once-and-forever given.”⁵

The scholarship on Eisenstein is gradually catching up with the significance of his long-overlooked and actively erased queerness, allowing it to shine new light on his films and writings. In a recent article for October (a journal that was named, in the 1970s, after Eisenstein’s celebratory film about the October Revolution), Elena Vogman looks at how Eisenstein’s theories of sexuality and ecstasy feed into a provocative reconceptualization of Marxist dialectics, opening up the possibility of a queer dialectics, a sexy dialectics, a dialectics that moves away from teleology and that can, in Vogman’s words, “abandon logic as a modus operandi of dialectics, not least by multiplying and dissolving the stability of binary relations and gender codes.”⁶

Writing in his diary in 1931 in Mexico, Eisenstein claimed that “a physical predisposition towards dialectics | especially towards the one experienced through emotions, i.e., the ecstatic one | is connected, to a lesser or greater degree, to bisexuality.”⁷ Bisexuality was Eisenstein’s term for a state of sexual nondifferentiation — one that allowed for oscillation and change. Vogman recounts how, also in 1931, Eisenstein wrote a letter to the early gay and trans rights advocate Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld — director of the Institute for Sexual Research, which Eisenstein had previously visited in Berlin — to share his theories of bisexuality and dialectics, and to request from Dr. Hirschfeld an “outline of Hegel’s (the father of the modern dialectic) sexual type with particular emphasis on possible (and to what extent expressed) traces of bisexuality in him.”⁸

!!! Skipping past Marx and going right back to Hegel, Eisenstein searches, outlandishly, for an understanding of the European dialectical method as something with a basis in somatics, in the ecstatic, in the elasticity of horny nondifferentiation. And this is part of what pulses in his sex drawings, when they show a world horny for sex but also horny for transformation.

- Eisenstein on Disney, edited by Jay Leyda, translated by Alan Upchurch (London: Methuen, 1988), p. 57.

- Ibid. p. 57.

- Ibid. p. 4.

- Ibid. pp. 3-4.

- Ibid. p. 33.

- Elena Vogman, “Visceral Economies, Queer Dialectics: Eisenstein Meets Bataille,” October 188 Spring 2024, pp. 117–148; p. 146.

- Sergei Eisenstein, diary from Mérida, Yucatán, March 1931, in Rebecchi and Vogman, Sergei Eisenstein and the Anthropology of Rhythm (Rome: NERO editions, 2017), p. 49.

- Eisenstein cited in Vogman, “Visceral Economies, Queer Dialectics,” p. 145 (emphasis in original).